Why Audit Trails Fail: Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Audit trails are fundamental to trustworthy systems, yet many organisations struggle to build them correctly. Even well intentioned engineering teams make mistakes that cause their audit trails to fail under pressure. These failures often do not surface during normal operation. They appear only during security incidents, customer disputes, certification audits, or compliance reviews.

This article examines why audit trails break down, what problems they tend to exhibit in real systems, and how to design audit infrastructures that avoid these pitfalls entirely.

What Does It Mean for an Audit Trail to Fail

An audit trail fails when it can no longer provide an authoritative, complete, or trustworthy record of events. Failure occurs when the audit trail:

- Omits important events

- Includes inaccurate or inconsistent data

- Is susceptible to tampering or retroactive editing

- Lacks structure or schema discipline

- Cannot be queried reliably

- Stores sensitive data that violates compliance expectations

- Cannot stand up to external scrutiny

When these failures occur, the organisation loses its ability to answer the key question that audit trails exist to support:

What exactly happened, when did it happen, and who performed the action

Failure 1. Missing Events

The most common reason audit trails fail is simply that events are not logged consistently. Engineering teams often log events manually across many services. As the system evolves, new features are added without corresponding audit events, causing gaps.

Missing events lead to:

- Incomplete timelines

- Doubt during investigations

- Problems reconstructing user journeys

- Inability to demonstrate compliance

How to prevent it

- Create a unified event taxonomy

- Define required events for every critical action

- Incorporate audit logging into acceptance criteria

- Provide a central audit logging SDK

- Enforce schema validation

Failure 2. Inconsistent Schemas

If different services log events in different formats, it becomes impossible to query or correlate them. This problem grows exponentially in microservice environments.

Inconsistent schemas cause:

- Fragmented event histories

- Complicated query logic

- Higher risk of missing details

- Increased forensic investigation time

How to prevent it

- Use a centralised schema

- Implement strong validation

- Use linting or CI enforcement

- Provide code generation or SDKs

Failure 3. Storing Sensitive Data

Audit logs often leak sensitive information because engineers log entire payloads, request bodies, or database rows. This can violate regulations and increases organisational risk.

Examples of sensitive data that should not be logged:

- Passwords or password hashes

- Authentication tokens

- Personal data such as addresses or emails

- Payment information

- Health records

- Private messages

How to prevent it

- Apply strict minimisation policies

- Log only what is strictly required

- Redact or pseudonymise fields

- Avoid storing raw payloads

- Apply field level whitelisting

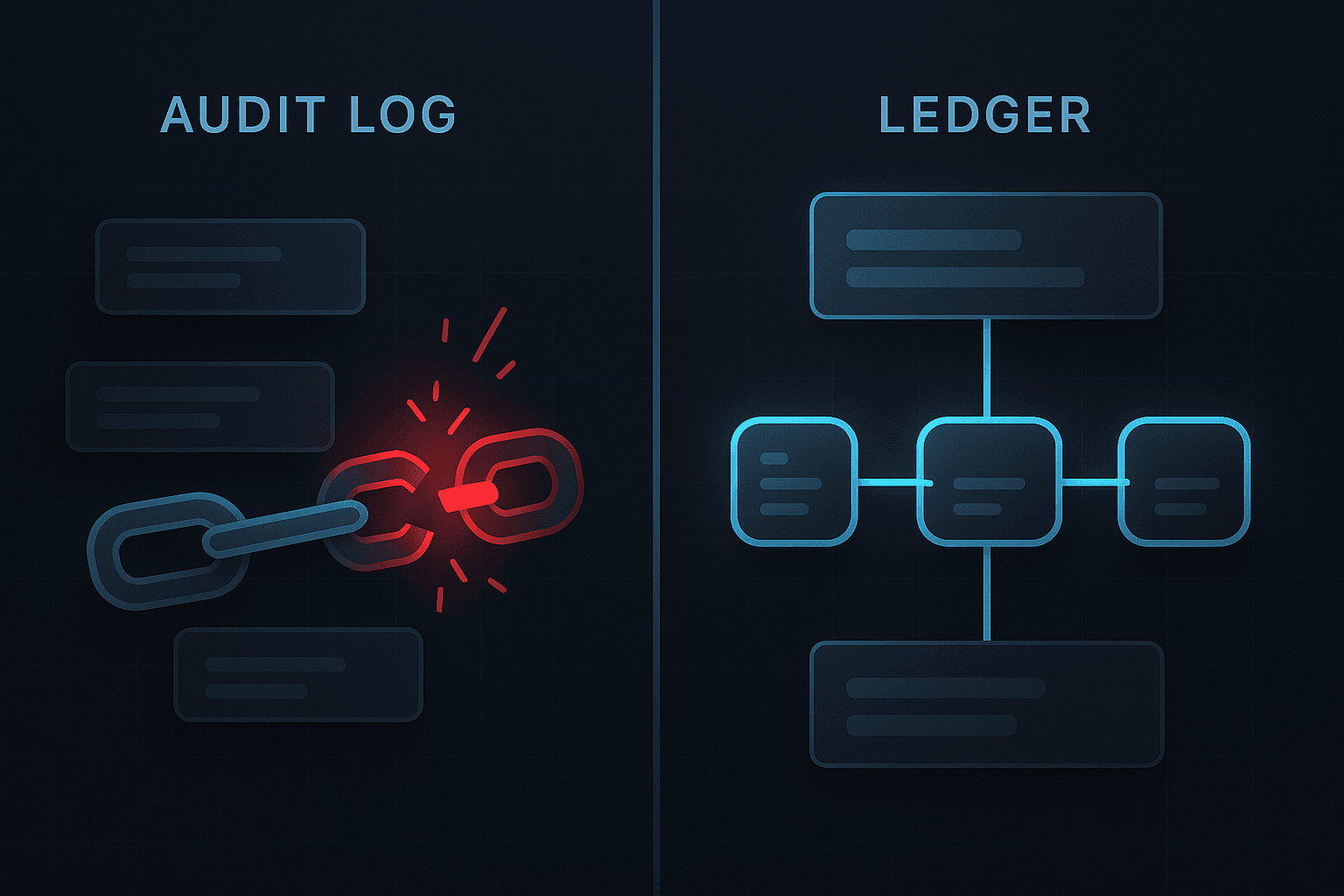

Failure 4. No Immutability Guarantees

Many systems store audit logs in places where data can be modified or deleted. Sometimes it is as simple as allowing log rotation to remove files that should be preserved.

Without immutability:

- Evidence loses credibility

- Incidents cannot be reconstructed accurately

- Malicious actions may go unnoticed

- Auditors question the reliability of the system

How to prevent it

- Use hash chained ledgers

- Sign events cryptographically

- Prevent deletion or modification

- Log access to audit logs

- Use append only storage systems

Failure 5. Weak Access Controls

Audit logs often contain sensitive operational data. If too many people can access them, the risk of misuse increases.

Overexposure of logs can result in:

- Internal threats

- Data leakage

- Accidental access to personal information

- Compliance violations

How to prevent it

- Role based access controls

- Segregation of duties

- Logging of audit log access

- Strictly limited administrative privileges

Failure 6. Lack of Retention and Lifecycle Management

Many organisations store audit logs indefinitely. Long term retention increases risk and may even violate regulations such as GDPR.

Problems caused by poor retention discipline:

- Excess storage costs

- Increased risk exposure

- Accumulation of unnecessary personal data

- Difficulty fulfilling deletion requests

How to prevent it

- Define a retention policy per event type

- Use automated deletion or archival

- Document legal requirements clearly

- Avoid infinite retention unless required

Failure 7. Over Coupling to Infrastructure

When audit logs depend too closely on infrastructure components such as specific servers or containers, system migrations or scaling efforts break continuity.

This causes:

- Fragmented logs

- Lost history during migrations

- Difficulties maintaining lineage

- Gaps in compliance evidence

How to prevent it

- Use centralised logging

- Decouple audit events from runtime instances

- Send events to a dedicated audit service

Failure 8. No Clear Ownership

Audit trails often drift because no team owns them. As a result, they fail to evolve as the system matures.

Consequences include:

- Missing events

- Poor documentation

- Lack of consistency

- Slow response to new regulatory needs

How to prevent it

- Assign explicit ownership

- Establish audit governance processes

- Conduct regular reviews

Failure 9. Difficult or Unusable Querying

In many organisations, audit logs technically exist but are effectively unusable. If the system cannot query events quickly or reliably, investigations break down.

How to prevent it

- Structure events in JSON

- Index events by key fields

- Provide APIs for search

- Pre compute common filters

- Design for investigations, not storage

Designing Audit Trails that Resist Failure

A strong audit trail system is intentional. It follows several design principles:

Principle 1. Centralisation

All audit events should flow into a single system, even if generated by several services.

Principle 2. Schema Discipline

Events must follow a consistent structure across the entire organisation.

Principle 3. Minimalism

Only record what is necessary for accountability.

Principle 4. Immutability

Historical events must be preserved and tamper evident.

Principle 5. Controlled Access

Only authorised roles should be able to view audit logs.

Principle 6. Lifecycle Management

Retention periods must match regulatory and business requirements.

Principle 7. Traceability

It must be possible to follow a complete user or resource journey with clear continuity between events.

How HyreLog Helps Prevent Audit Trail Failure

HyreLog is designed to prevent the failures described in this article by providing:

- Strict event schemas

- Immutable hash chained storage

- Region aware hosting

- Centralised ingestion

- Fine grained API keys

- Enforced retention

- Exportable forensic packages

- Developer friendly integration

Organisations can avoid building fragile or insecure audit infrastructures and instead adopt a reliable, purpose built solution.

Conclusion

Audit trails fail for predictable reasons. Missing events, inconsistent schemas, weak access controls, and the lack of immutability all undermine the purpose of audit logging. By understanding these pitfalls and designing systems around clarity, structure, and integrity, organisations can build audit trails that withstand scrutiny and support their operational and compliance needs.

Strong audit trails do not happen by accident. They require intention, structure, and investment. With the right approach, teams can avoid failure and maintain a trustworthy record of system activity.